(Berlin) – Azerbaijani forces have inhumanely treated numerous ethnic Armenian military troops captured in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, Human Rights Watch said today. They subjected these prisoners of war (POWs) to physical abuse and humiliation, in actions that were captured on videos and widely circulated on social media since October.

The videos depict Azerbaijani captors variously slapping, kicking, and prodding Armenian POWs, and compelling them, under obvious duress and with the apparent intent to humiliate, to kiss the Azerbaijani flag, praise Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, swear at Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, and declare that Nagorno-Karabakh is Azerbaijan. In most of the videos, the captors’ faces are visible, suggesting that they did not fear being held accountable.

“There can be no justification for the violent and humiliating treatment of prisoners of war,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Humanitarian law is absolutely clear on the obligation to protect POWs. Azerbaijan’s authorities should ensure that this treatment ends immediately.”

Although some of the prisoners depicted in videos Human Rights Watch reviewed have, in subsequent communications with their families, said they are being treated well, there are serious grounds for concern about their safety and well-being.

International humanitarian law, or the law of armed conflict, requires parties to an international armed conflict to treat POWs humanely in all circumstances. The third Geneva Convention protects POWs “particularly against acts of violence or intimidation and against insults and public curiosity.”

The armed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh escalated on September 27, 2020, with Azerbaijan’s military offensive. Hostilities ended on November 10 with a Russia-negotiated truce.

While exact numbers are unknown, Armenian officials in Yerevan told Human Rights Watch that Azerbaijan holds “dozens” of Armenian POWs. Armenia is known to hold a number of Azerbaijani POWs and at least three foreign mercenaries. Human Rights Watch is investigating videos alleging abuse of Azerbaijani POWs that have circulated on social media and will report on any findings.

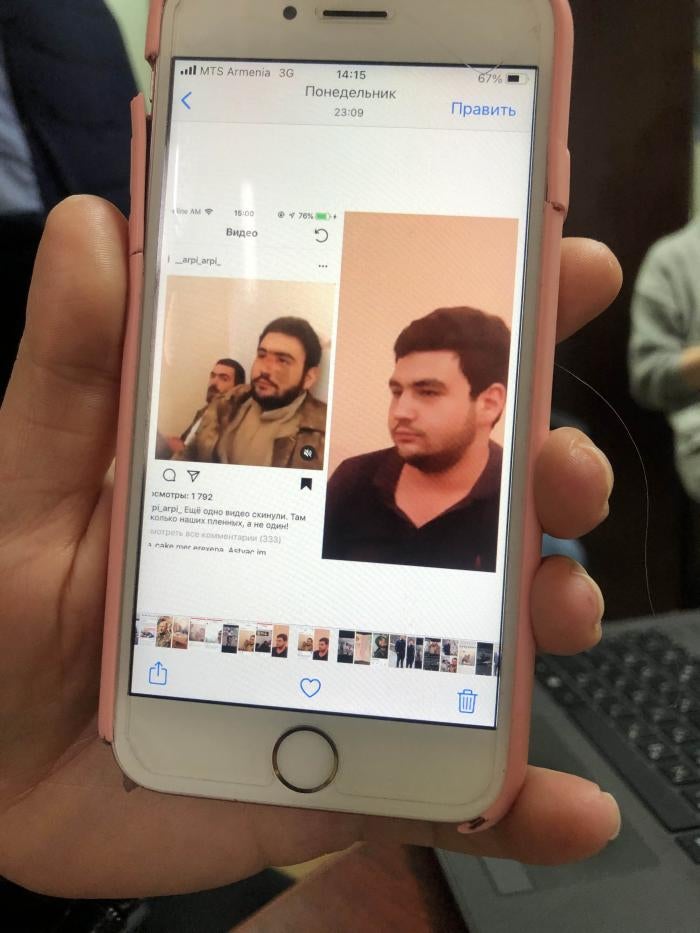

Dozens of videos alleging abuse of Armenian POWs have been posted to social media. Human Rights Watch closely examined 14, and spoke with the families of five POWs whose abuse was depicted. The videos were posted to Telegram channels, including Kolorit 18+ and Karabah_News, and to several Instagram accounts. None of the videos have metadata that could confirm the time and location where they were recorded attached, as it was stripped when the videos were uploaded to Telegram and other platforms. But Human Rights Watch is confident that none of these videos were posted online before October-November 2020.

Human Rights Watch also examined numerous other images and legal documents, and spoke with two lawyers, Artak Zeinalyan and Siranush Sahakyan, who represent the families of close to 40 POWs in requests filed with the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) for interim measures (urgent measures to protect people whose cases are pending with the court and who are at “imminent risk of irreparable harm”). The court granted all the requests on behalf of individual POWs to instruct the Azerbaijan government to provide information on the POWs, the lawyers said.

The families confirmed that they saw their loved ones in the videos, provided photographs and other documents establishing their identity, and confirmed that these relatives were serving either in the Nagorno-Karabakh Defense Army, or the Armenian armed forces.

Sergey Martirosyan lost contact with his son, Michael, 21, after an October 17 phone call. On October 25, Sergey saw a video on Telegram depicting eight Armenian soldiers abused by Azerbaijani military. The soldiers lay on the ground, blindfolded and restrained, as their captors kicked, dragged, and stepped on them, and prodded them with a sharp metal rod. At the 1:28 mark, the camera zooms in on a soldier who repeats, moaning, “I will tell everything,” in Russian, as Azerbaijani soldiers kick him at least seven times, step on his head and leg, and prod him.

Sergey said he immediately recognized his son’s voice, physique, hair, and certain facial features. He contacted the ICRC and local authorities. On November 9, after the ECtHR’s intervention, Sergey received a brief phone call from Michael, who said he was being held in Azerbaijan and receiving treatment for leg wounds in a medical facility.

Hranush Shahbazyan lost contact with her husband, Ludvig Mkrtchyan, 51, after an October 13 phone conversation. On November 12, her husband’s brother sent her the same video in which Martirosyan appears. She recognized Mkrtchyan’s voice, bald head, and physique. When the video opens, Mkrtchyan is lying curled up on his side, with his stomach and back partly exposed, and an apparent puncture wound on the left side. During the 00:58–1:25 segment, two Azerbaijani soldiers repeatedly kick and poke him with the metal rod on his head, back, stomach, and legs, as he pleads with them not to hurt him.

According to Shahbazyan, on November 20, after the ECtHR’s intervention, the ICRC informed her that they visited her husband. Shahbazyan showed Human Rights Watch a letter she received that Mkrtchyan had dictated. Shahbazyan said she was reassured of his identity when a few days later he confirmed the pet name for their daughter.

The lawyers said that family members who are their clients had identified three other servicemen depicted in the video: Valery Hayrapetyan, Arman Harutyunyan, and Armen Martirosyan (not related to Michael Martirosyan).

Shirak Sargsyan lost contact with his son, Areg, 19, on October 2. On October 8, a relative alerted the family to two videos that show Areg lying on top of an Azerbaijani tank and then sitting on the same tank and, on his captor’s orders, shouting “Azerbaijan” and calling Pashinyan names.

In mid-October, three more videos with Sargsyan appeared on social media. One shows Sargsyan, apparently on the back seat of a vehicle, wearing a flowery smock and a thick black blindfold, and repeating, on his captors orders, “long live President Aliyev,” and “Karabakh is Azerbaijan,” and cursing Pashinyan. Sargsyan’s family and lawyers also saw him in a news story by the Azerbaijani broadcaster Kanal 1: sitting in a hall, looking disoriented and distressed, he speaks under duress, condemning Pashinyan, including for sending him to war. His voice shakes, his breathing is heavy, and his lower legs are bandaged.

Sargsyan’s family said that on October 17, Azerbaijani authorities facilitated an ICRC visit with him. He was allowed to write a letter to his family twice and to call them briefly on October 17.

On October 18, Azerbaijani media and official sources reported that government officials visited three captured Armenian servicemen, including Sargsyan, in a hospital where they appeared to be getting medical treatment. The servicemen, who were photographed and filmed on video, expressed “gratitude” for their treatment.

On October 22 and 23, at least six videos were circulated on social media showing five captured Armenian soldiers ill-treated and humiliated by Azerbaijani servicemen. In the videos, the Azerbaijani captors, dancing, apparently in celebration of a military victory, slap one of the prisoners on the head, make them kneel, clap, and say “Karabakh is Azerbaijan,” and force at least three of the prisoners to kiss the Azerbaijani flag. Zeinalyan and Sahakyan, the lawyers, said that the prisoners’ relatives contacted them, identifying the five as Eric Khachaturyan, Robert Vardanyan, Narek Sirunyan, Arayik Galstyan, and Karen Manukyan.

Human Rights Watch spoke with family members of Khachaturyan, 18, and Vardanyan, 20.

Khachaturyan’s father, Saribek, lost contact with his son on October 12. Several days later he learned that his son had been wounded. He had no further information until November 22, when a neighbor showed him a video in which he recognized Eric. Later, the family saw him in another four videos. The videos show Eric’s captors holding him by the neck and slapping his head as they attempt to force him to say “Karabakh is Azerbaijan,” to kiss the Azerbaijani flag, and to kneel and clap, together with Vardanyan and another prisoner, as their captors are dancing.

Robert Vardanyan’s mother, Varduhi Parunakyan, said that her last contact with her son was on October 8. Later, she learned that Vardanyan had been wounded and that he, together with Khachaturyan and three others, were captured while awaiting a rescue team.

In the videos, Vardanyan is forced to kiss the Azerbaijani flag after Khachaturyan and another prisoner have done so, kneel on the ground and clap, together with Khachaturyan and another prisoner, as their celebrating captors are dancing; and to say repeatedly “Karabakh is Azerbaijan.” In the “Karabakh is Azerbaijan” video, he is indoors, his face is bruised and dirty, and one of his captors is pressuring him to speak louder; whereas in the “celebration” video he is outdoors and his face is clean and unmarked by bruises.

On November 27, the ECtHR requested information from Azerbaijani authorities regarding the five soldiers’ whereabouts. Azerbaijan has not yet provided a response.

“It is telling that some of the servicemen who carried out these abuses had no qualms about being filmed,” Williamson said. “Whether or not the soldiers thought they would get away with it, it is essential for Azerbaijan to prosecute those responsible for these crimes on the basis of both direct criminal liability and command responsibility.”